News / Indefensible? How Government told Parliament about the Strategic Defence Review - Parliament Matters podcast, Episode 95

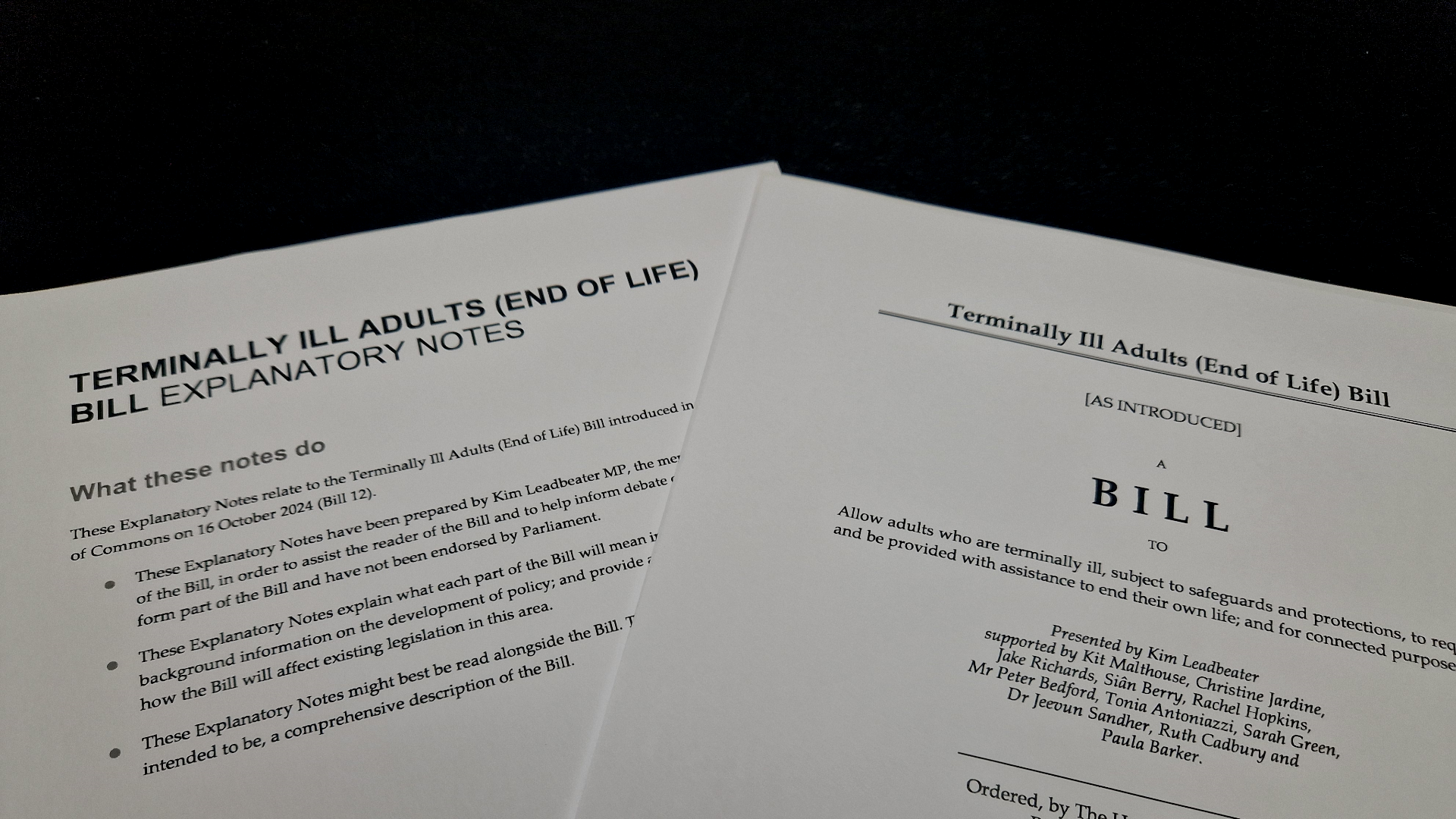

In this episode, we explore why ministers keep bypassing Parliament to make major announcements to the media — and whether returning to the Despatch Box might help clarify their message. We unpack the Lords' uphill battle to protect creators’ rights in the Data Use and Access Bill, challenge claims that the Assisted Dying Bill lacks scrutiny, and examine early findings from a Speaker’s Conference on improving security for MPs, as threats and intimidation against politicians continue to rise. Please help us by completing our Listener Survey. It will only take a few minutes.