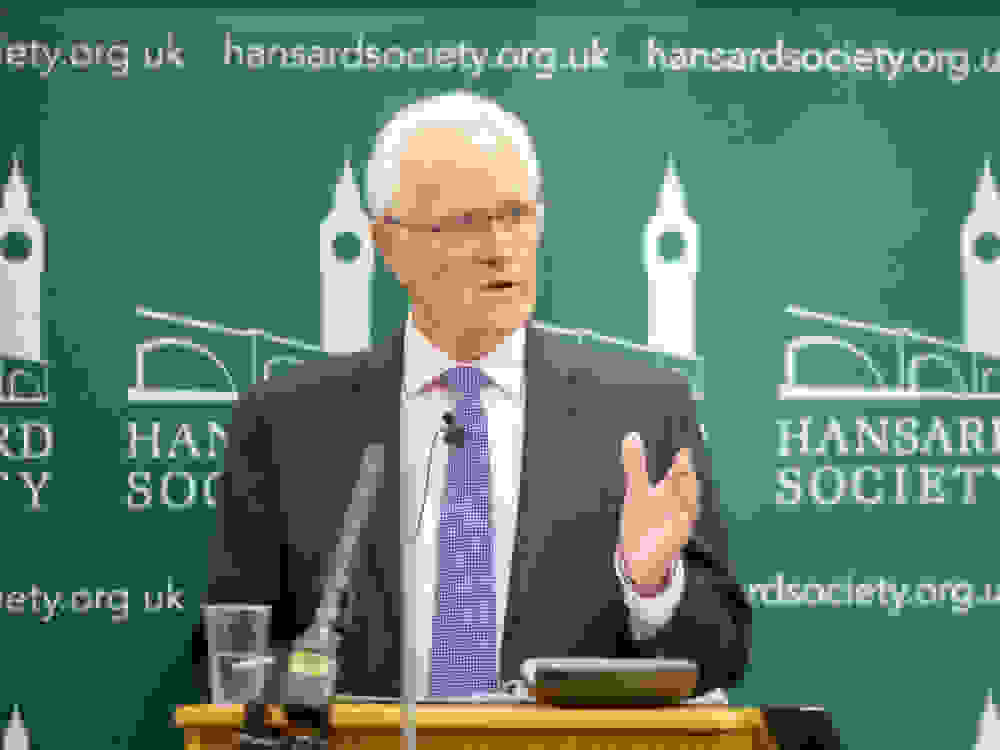

Members / Parliamentary Affairs 75th Anniversary Lecture: The Lord Speaker on the future of the House of Lords

At this members' event, the Lord Speaker set out his thoughts on the future of the House of Lords, addressed concerns regarding the size of the Upper House, set out the benefits of the House's scrutiny work, and considered the constitutional role of the House and its role in our wider society. 7:30pm–8:30pm, 7 December 2022 Members' event (Westminster)