Data / Addresses to both Houses of Parliament

Addresses to both Houses of Parliament can be important elements both of UK national occasions and of visits by major foreign dignitaries. Who gives them, and where? Last updated: 3 December 2024

How can a Parliament fulfil its democratic functions in a state of total war? Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s Parliament has worked uninterruptedly and fulfilled vital legislative, diplomatic and symbolic functions. But, a year on, it continues to seek the happy medium between maximising national security, and ensuring the transparency necessary for continued democratic functioning.

Dr Sarah Whitmore

Reader in Politics, Oxford Brookes University

Sarah Whitmore is a Reader in Politics at Oxford Brookes University. She completed her PhD on the first decade of institutional development of Ukraine’s parliament at the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Birmingham, where she also held an ESRC post-doctoral fellowship. She has a long-standing interest in legislative politics and has published peer-reviewed research on Ukrainian and Russian parliamentary and party politics, including State-Building in Ukraine: The Ukrainian Parliament (Routledge, 2004). Her current British Academy-funded research project (together with Professor Bettina Renz at the University of Nottingham) is investigating the importance of the political and strategic context for military reform in Ukraine. A second focus is Ukrainian state functioning during war.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

We will never share your data with any third-parties.

Share this and support our work

The wartime operation of Ukrainian state institutions has largely exceeded expectations in general, and estimations of state capacity in particular. The performance of Ukraine’s Parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, has perhaps been most startling of all.

At the start of the war, some Ukrainians even anticipated that MPs would simply flee abroad. Instead, the vast majority stayed and worked. The Rada continued to hold plenary sessions in person, adopting legislation to put Ukraine on a war footing, even when the Russian military was only 20 kilometres from Kyiv, and MPs were known to be targets. A constitutional majority of over 300 MPs have continued to gather in the chamber to take democratic decisions to respond to the exigencies of total war.

The uninterrupted functioning of Ukraine’s democratically-elected Parliament, in the face of full-scale invasion and imminent threat to life, probably marks the post-1991 Rada’s institutional high-point. Parliament’s continued operation was crucial for legitimate decision-making, especially given the gravity of the decisions being taken, which necessarily impinged on citizens’ democratic freedoms (such as introducing martial law, military conscription and restrictions to freedom of movement). It also conveyed symbolic legitimacy – which was important both domestically, for morale, and internationally, to demonstrate the continuity of democratically-elected institutions.

Even some MPs were surprised at how many of their colleagues (especially the pro-Russian ones) came to the chamber of the Rada in the first days of the war. Citizens tended to have even lower expectations: the Rada has consistently been rated as one of Ukraine’s least-trusted institutions, with a staggering -76% rating in 2016 – exceptionally low in global comparative terms.

Why did MPs stay working after the outbreak of the war, if they are as rapacious and self-serving as Ukrainian citizens believed?

At least in part, Ukrainians’ negative opinions about the Rada were grounded in some misperceptions about how much had changed. This applied especially since the 2019 elections, when President Volodymyr Zelensky’s party ‘Servant of the People’ (named after the TV show in which he starred) won independent Ukraine’s first overall parliamentary majority, and 78% of the MPs elected were fresh faces. Like President Zelensky, many new MPs were part of what Olga Onuch and Henry Hale (in their book The Zelensky Effect) call the ‘Independence Generation’ – that is, those who had come of age politically as Ukrainian, not Soviet, citizens. The post-2019 Rada also had more women than ever before (20%), more civic activists and reduced influence by oligarchs. Procedural changes followed which limited MPs’ immunity, absenteeism and ability to hire their relatives.

Then, in the first days of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, the most profound existential crisis provoked in Ukrainians across the country a strong desire to make a positive contribution. This surely included most MPs.

Consequently, since the start of the war the Rada’s trust rating has - like that of other state institutions - improved dramatically: from -56% in December 2021 to +2% in December 2022. Nevertheless, the Parliament remains one of the least-trusted state institutions, with only the courts and the procurator ranking lower.

While Parliament continued working, it did not do so quite as normal. The experience of Covid-19 meant that most parliamentary business could be conducted online, yet plenary sessions were always conducted in person, in shortened form, for security reasons. Decisions were adopted by huge cross-party majorities, nicknamed the ‘Defence Coalition’.

A year later, this remains true of key decisions on, for example, security questions. However, after Russian troops retreated from Kyiv in April 2022, Ukrainian parliamentary politics re-emerged, and wartime institutional adaptation blended with more familiar features.

Despite - or rather because of - the war, Parliament managed to adopt a record number of laws: 229 during the Spring 2022 session. This surpassed all previous convocations. A consensus was worked out before a Bill was put on the agenda, permitting plenary examination to be incredibly fast: 90% of Bills passed in less than two minutes of floor time, and 50% of Bills with fewer than eight days between initiation and adoption.

Concerns from civil society and independent media about the ‘turbo-mode’ of the legislative process had been a feature of the first year of Zelensky’s Presidency (2019-20). The resurgence of the phenomenon was initially accepted due to the emergency of the invasion. However, towards the end of 2022, worries resurfaced about a large number of procedural violations (even if most were minor), ongoing reductions in transparency, and haste affecting legislative quality.

Predictably, legislative priorities concerned martial law, defence/security, international appeals and supporting the economy. Perhaps more surprising was the considerable attention paid to EU integration legislation.

Ukraine’s progress on EU integration was especially important because it provided Ukrainians with a vision of a post-war future that was democratic, liberal and an intrinsic part of Europe. Ukraine applied to join the EU in February 2022 and the European Council granted the country official candidate status in record time in June.

Fully 50 laws necessary for integration with the EU were adopted during 2022. Some had been in preparation for a long time and did not provoke particular controversy. Others went to the heart of the separation of powers in Ukraine, an issue which successive Presidents have sought to resolve in their favour. Judicial reform has long been such an issue. To give just one example: the Rada passed, and - despite the objections of the European Commission - President Zelensky signed, a law that sought to preserve presidential influence over the appointment of Constitutional Court judges. Just as under his predecessor, there thus remained tensions within Zelensky’s administration about the European path, and progress was slower than headline figures suggested. Nevertheless, the overall European direction of travel was clear.

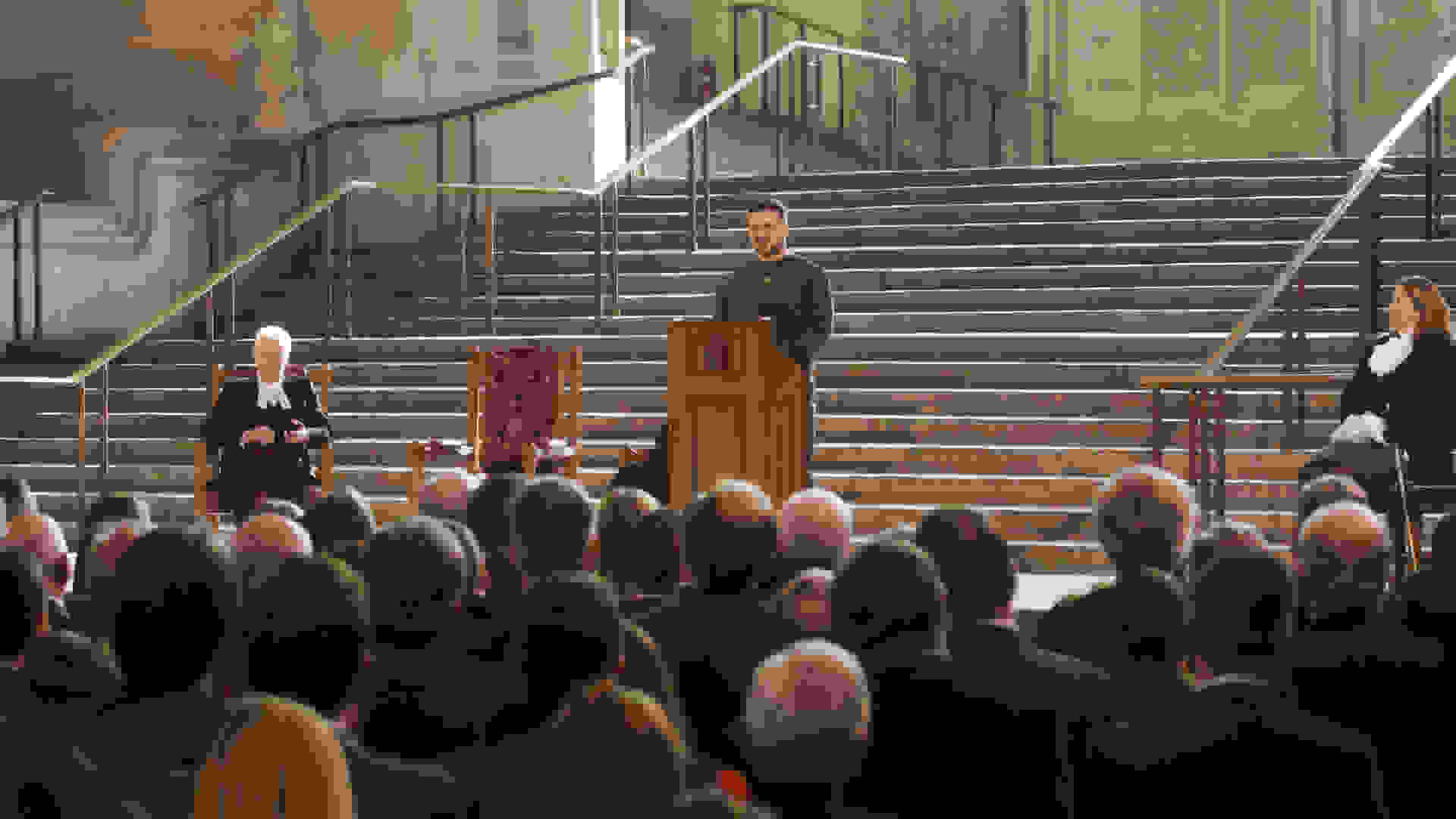

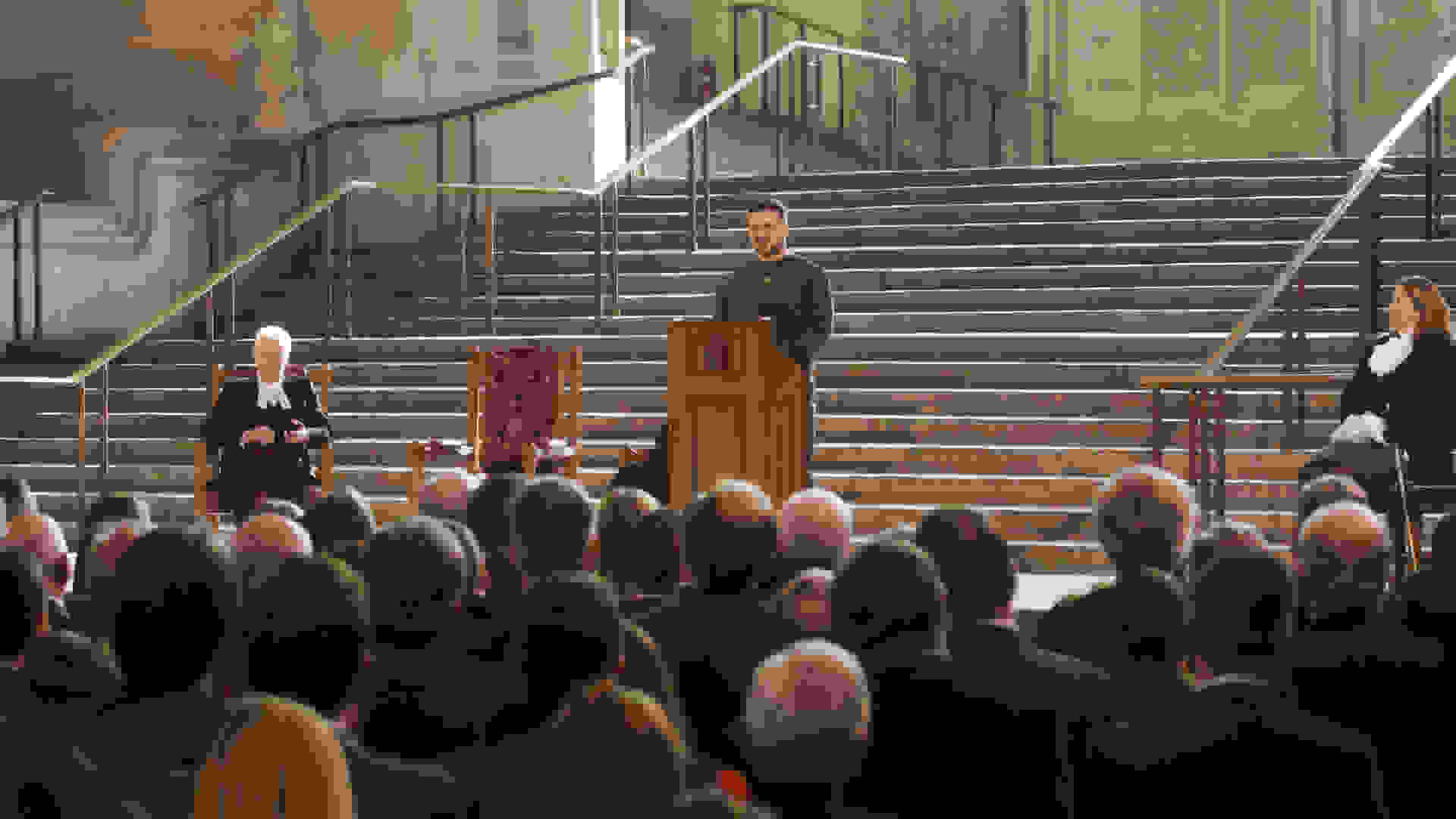

A regular portion of plenary agenda time was devoted to making appeals to international organisations, such as the recent request to exclude Russia from the 2024 Olympic Games. The plenary also heard speeches from world leaders, and the Parliament welcomed a succession of international visitors. MPs were also active in international parliamentary delegations, and joint parliamentary committee meetings were held with international counterparts. In effect, full-scale war necessitated the Rada’s development for the first time into a genuine forum for international delegations.

Addresses to both Houses of Parliament can be important elements both of UK national occasions and of visits by major foreign dignitaries. Who gives them, and where? Last updated: 3 December 2024

If the scale of the threat produced a consensus on the need to control information around parliamentary business, this quickly became an area of tension that escalated as the war dragged on.

The parliamentary TV channel ‘RADA’ was prohibited from broadcasting live parliamentary sessions during martial law, for clear security reasons; but such concerns were rather less evident in the channel’s sudden detailed coverage of the activities of presidential staff. When it came to the mainstream national television channels, parliamentary opposition factions such as former President Poroshenko’s ‘European Solidarity’ and ex-Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko’s ‘Fatherland’ found their access to the wartime national unified broadcast limited, while it welcomed erstwhile pro-Russian MPs who were now voting with the President’s party to prop up its majority. The continued presence of the latter in the Rada was itself an ongoing security concern and a focus for MPs’ and public consternation.

Reduced transparency on security grounds also provided cover for those MPs who wished to hide their unexplained wealth – although they did not necessarily succeed, owing to Ukraine’s indefatigable investigative journalists. For MPs from President Zelensky’s party, disciplinary action followed such efforts, especially as such behaviour was regarded as politically intolerable during wartime.

Overall, steps (both systematic and ad hoc) are now being taken to address transparency concerns. In addition, individual MPs used social media (especially Telegram) to bring greater transparency to Parliament’s actions. In the absence of journalists in the Rada chamber, this became a vital source of information.

Some parliamentary committees managed to maintain a high degree of transparency in their work, but this varied considerably.

Parliamentary oversight activities became a reduced priority, but committee work in this area continued. Ministerial reports, ex ante review of candidates for public office and consideration of interpellations took place during online meetings; but, as is typical for the Rada (and many other legislatures), much oversight activity is down to the initiative of individual MPs, and therefore can be patchy. In January 2023, Defence Committee Member Serhiy Rakhmanin opined that due to the combination of a single-party majority and war, Parliament had effectively delegated its oversight functions to the Government and had become what every Ukrainian President had dreamed of – a legislative arm of the Presidential Office. However, in the wake of a defence procurement scandal broken by independent journalists in January, and the subsequent tidal wave of public anger, both the President and Parliament were compelled to take swift action. The Defence Committee hosted an urgent meeting with key officials from the Ministry of Defence and took steps to strengthen its budgetary oversight activities.

Despite wartime restrictions and a presidential majority party, Ukrainian parliamentary politics remain messy, pluralistic and sometimes inconvenient for the presidential branch of power.

Overall, alongside Parliament, some of the most significant wartime oversight of the Government has continued owing to civic activism – that is, monitoring and investigations by civil society and independent media. However, the recent cluster of scandals across a number of departments and levels of government demonstrates the need for constant parliamentary oversight, and offers scope for deputies (including from the President’s party) to contribute positively to democratic governance.

The exigencies of war engender profound challenges in democratic relations, as notions of security conflict with transparency, and state responsiveness sits in tension with procedural norms.

After a year of war, the Verkhovna Rada has, like the rest of the country, continued to work. It has adopted a huge volume of legislation to put Ukraine on an indisputably-legitimate war-footing, while also performing important diplomatic and symbolic functions, and moving Ukraine forward on the path towards EU membership. Nevertheless, civil society and MPs themselves have raised questions about the prolonged limits to the transparency of parliamentary operations.

As a state institution in wartime, the Verkhovna Rada continues to seek the happy medium between maximising national security and ensuring the transparency necessary for continued democratic functioning. In this Sisyphean task, the monitoring efforts of Ukraine’s civil society, independent investigative journalists and a critical core of ‘workhorse’ MPs play a key role.

Whitmore, S. (23 February 2023), Ukraine’s Parliament: One year at war (Hansard Society blog)

In our latest ‘Whipping Yarn’, we talk with Simon Hart, former Conservative Chief Whip during Rishi Sunak’s Premiership. Hart opens up about his time in one of Westminster’s most demanding and discreet roles, chronicled in his new book, ‘Ungovernable: The Political Diaries of a Chief Whip’.

If a crisis or major national event occurs during a period when Parliament is adjourned, there are often demands from MPs, the media and the public for Parliament to be ‘recalled’. But the House of Commons Standing Orders stipulate that only Government Ministers - in reality, the Prime Minister - can ask the Speaker to recall the House. In recent years the House of Lords has generally been recalled at the same time as the House of Commons.

In response to the Modernisation Committee's call for views on 17 October 2024, we submitted evidence outlining key areas we believe the Committee should prioritise. Our submission recommended a focus on: strengthening legislative scrutiny, with particular emphasis on reforming the delegated legislation system; enhancing financial scrutiny, especially in relation to the Budget and the Estimates; addressing strategic gaps in parliamentary scrutiny; making more effective use of parliamentary time; and reviewing the Standing Orders, language and rituals of the House of Commons.

This briefing explains what to watch for during the Second Reading debate of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill on 29 November. It outlines the procedural and legislative issues that will come into play: the role of the Chair in managing the debate and how procedures such as the 'closure' and 'reasoned amendments' work. It looks ahead to the Committee and Report stage procedures that will apply if the Bill progresses beyond Second Reading. It also examines the government's responsibilities, such as providing a money resolution for the Bill and preparing an Impact Assessment, while addressing broader concerns about the adequacy of Private Members’ Bill procedures for scrutinising controversial issues.

In this ninth instalment of our special mini-podcast series, we continue to explore the latest developments in the progress of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, often referred to as the assisted dying bill. We are joined by Dr Marie Tidball MP to discuss the amendments she has secured for a Disability Advisory Board and an independent advocate for people with learning disabilities.